from chateau park to recreational domain

Project "Veltem"

East of Bruges, you can find a small forest. It looks nothing special today, but has an exceptional history. This green lung is now frequented by hikers, athletes and playing children. But what they don’t know is that this old forest once looked completely different. After all, the Veltembos used to be a chateau estate. If you look through the trees of this wild forest today, you can still find traces of it. The first castle was built there back in the 16th century, but most of the clues recall the last Veltem castle, built during the First French Empire.

Below, we focus on this castle and its surrounding castle park. We describe how it came into being, decayed and changed into a recreational domain. For that, we return to 3 July 1803.

FRANÇOIS BERTRAM'S "CHATEAU DE VELTHEM"

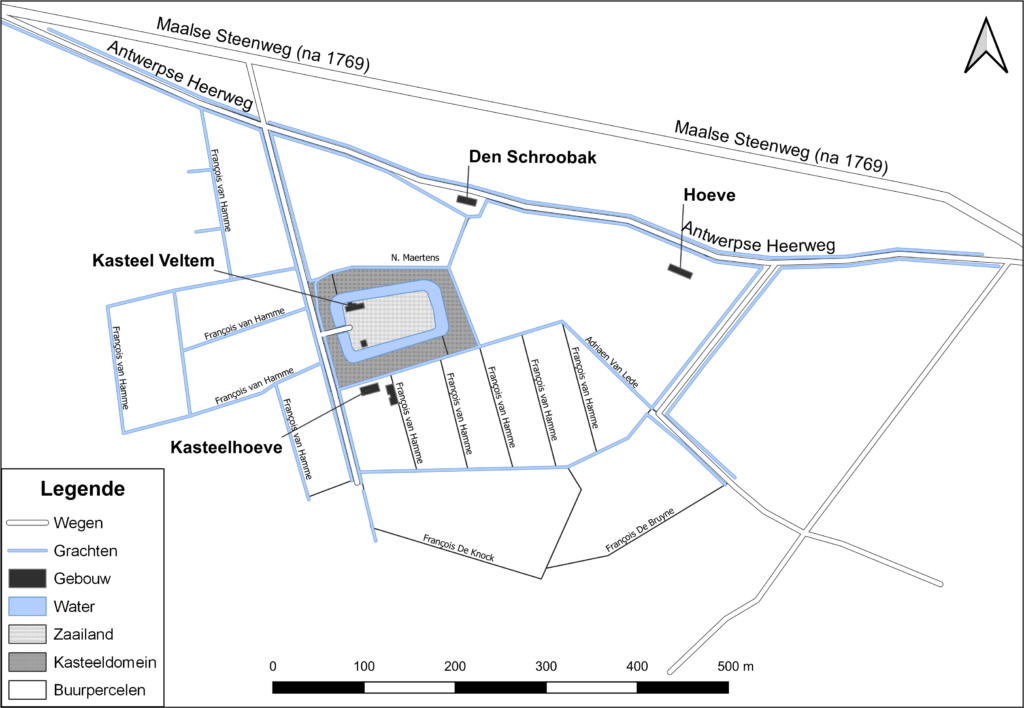

On this date, François Xavier Bertram and Denis Moles Le Bailly came to an agreement. The latter was the owner of the dilapidated Veltem castle estate in Sint-Kruis. Bertram was a Nieuwpoort shipowner and large landowner who had recently settled in Bruges. In his search for a pleasure domain outside the city walls, he bought the domain of Moles Le Bailly. By then, the walled estate already had a rich history. In the late 16th century, the Bruges alderman (and later mayor) Matthias Dagua built the first castle near the road junction between Antwerpse Heerweg and Sijselestraat. By 1803, however, not much remained of this. The buildings and the 18th-century French-style garden were dilapidated, the estate had been divided up and sold to different owners. What remained changed hands rapidly over half a century (Moles Le Bailly owned the estate for just a year).

With François Bertram, a new era began.

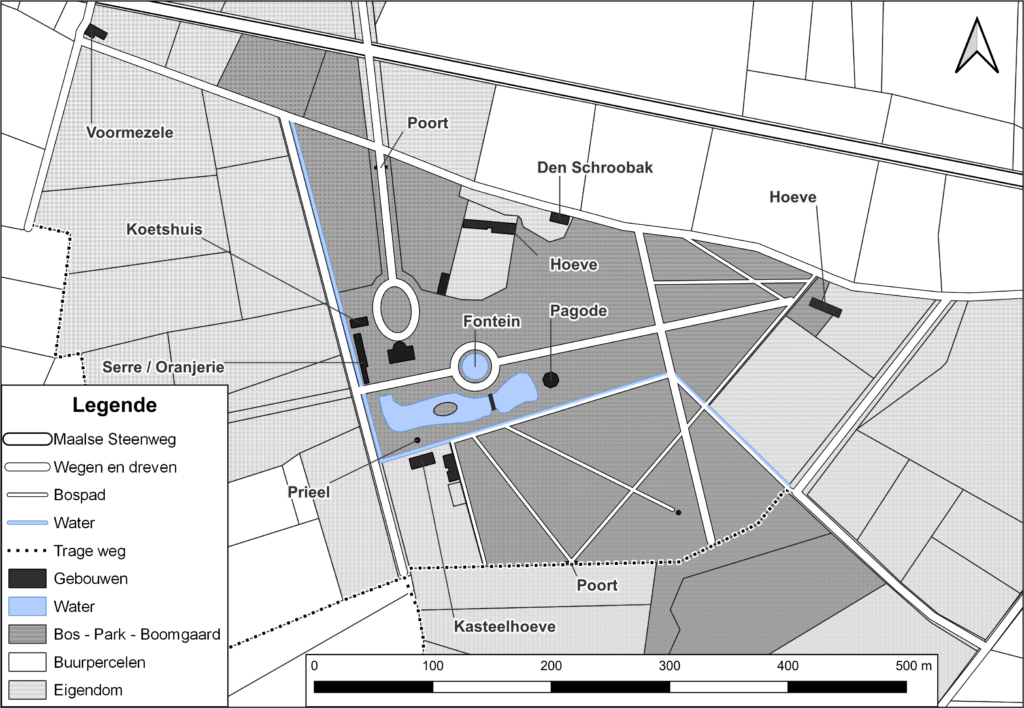

Between 1803 and 1826, the “Veltem” estate grew into an exceptional site. Bertram had the ruinous building demolished and built a new château in the modern Empire style, the style of the French Empire. This building – with a basement, ground floor, upper floor and attic – was characterised by a domed tower with belvedere. Around 1813, Joseph Denis Odevaere (later William I’s court painter) decorated this room with a ceiling painting of Apollo surrounded by the nine muses. Odevaere and Bertram knew each other as members of the lodge ‘La Réunion des Amis du Nord’. The interior was richly decorated with Empire furniture in mahogany, scarlet fabrics and gilded finishes. The staircase leading to the castle’s entrance was flanked by two sphinxes, a theme brought back from Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt. Bertram eventually succeeded in buying back the crumbled pieces of castle grounds and even expanded them. On this estate, he built his castle park, a showpiece that he opened to visitors. The baroque garden and farmland surrounding the castle gave way to a park “in the old Flemish style, with regular winding paths, foliage corridors of lime trees with openings like windows, and with long straight paths ending in studied vistas.”

Several of these paths can still be recognised today.

Bertram had a taste for Chinoiserie in addition to the style of the French Empire. The core of the castle park was around the ‘Chinese’ pond. This pond was the remnant of the old ramparts. He had the northern part filled in for the construction of the new castle drive, but recovered the pond to the south. The clean lines of this remnant moat were made more jagged and provided with a ‘green island’ (l’île verte), a coastal island overgrown with plants. A ‘Chinese’ bridge connected both sides. “At the end of the bridge” describes a visitor in 1817 “there is an artificial cave, decorated like a lion’s den, with the head of a stone lion peeping out of the entrance.” This cave had been built with recovered fieldstones taken from St Donaas Cathedral, demolished in 1799. Well into the 20th century, carved figures could be recognised among the stones. The cave was also equipped with a wine and ice cellar.

Atop this cave was an octagonal pagoda, about three storeys high. The top floor of this building had a water reservoir for the park’s fountains. Thus, a visitor in 1821 describes a basin in which colourful fish swim: “In the middle of this basin is a group of three statues, which are very beautiful [fort bonnes]; behind these statues is a fountain.” But there were other fountains hidden there. Apparently Bertram liked to tease his guests.

A new orchard with fruit trees is envisaged in the plans of Park Steevens. Actually, this is a return, as Bertram also owned an orchard on his property. However, his apple and pear trees were tightly pruned. His plant collection, however, did not stop at native plant species. Besides his interest in exotic architecture, Bertram had a penchant for exotic plants. His castle grounds were home to several greenhouses and a heated orangery. He cultivated peach trees and grapevines there, as well as exotic plants such as melons, pineapples and plumed cockscombs. One visitor describes the latter plants as follows: “[…] these [panicle combs] are the showpiece of Mr Bertrand’s garden [sic]: they are of the dwarf species, but large and strong for their kind; and in brightness and variety of colours they can hardly be surpassed.” Francois Bertram was a member of the ‘Brugsche Societeyt van Flora’ and participated annually in “the winter exhibition of the Bruges botanical flower-theatre” in February. His winning plants are illustrative of the exotic nature of his collection: a Japanese rose (Camellia japonica), an Anemone Arborea (Knowltonia tenuifolia) from South Africa, an Azalia Aurantiaca (Rhododendron calendulaceum) from the Appalachians in North America and a Mimosa Paradoxa (Acacia paradoxa) from Australia.

Continuity through the long 19th century

But everything comes to an end. At half past three in the morning on 9 February 1826, 59-year-old François Bertram breathed his last at his château. Bertram’s will did not leave his castle estate to his (second) wife, but to his daughter Catherine. In March 1826, the family drew up an inventory of the estate and in the summer months everything was sold publicly. Advertisements in ‘Gazette van Brugge’ show that everything goes under the hammer, not only the possessions of his shipping company in Nieuwpoort. At the castle, furniture, crockery, clothes, silverware and wines go out the door. Even the garden has to go. Garden benches, flower pots and a variety of plants from Aloes to Oleanders go to the highest bidder. The castle remains in use as a pleasure estate by Catherine and her husband Jacques Roels. The couple have three children-Pauline, Mathilde and Louise-but are not a long marriage. Catherine Bertram died in 1829, shortly after Louise was born.

She lived to be only 33.

As Pauline entered the convent, the castle went to his two other daughters after Jacques Roels’ death. Mathilde married Charles de Schietere de Lophem and lived in the castle for a while, but they later moved to Bruges. It is then the youngest of the three sisters – Louise Roels – who is the permanent occupant of the castle until her death in 1875. Thereafter, Charles and Mathilde Roels are again registered in the castle. Both are mentioned there until their deaths in 1894 and 1899 respectively. The public sale of their possessions provides another insight into the state of the castle grounds. For instance, the relatives sold a sizeable collection of plants, some more exotic than others: “11 large Lurians 100 years, 119 idem 4 years, 110 idem 3 years, 82 idem 2 years, 14 large Orangers, 4 large Calletreas, 2 large Myrtles, 9 Laurestines, 10 Formeas, 8 large Jucca, 25 Azalées, 12 Aloes, 48 Camelias, 6 large Palm trees.“

This illustrates the continuity of the castle estate in the 19th century.

Decay in the 20th century

THE FIRST WORLD WAR AND RECOVERY

In the early 1900s, the castle was occupied by Gabrielle de Schietere de Lophem, the daughter of Charles and Mathilde Roels. Although she was the official owner of the estate, the château was popularly given the name of her husband, Fernand de Séjournet de Rameignies. They lived there until World War I. When that war reached the region around Bruges in October 1914, the residents of ‘Kasteel de Séjournet‘ fled. Gabrielle tried in vain to hide her jewellery and silverware in the park’s cave, but they were discovered and stolen. The castle did not escape the billeting of German troops. The earliest mention of this dates from April 1915, when the Kraftwagenkolonne (motorised transport) took up residence in the castle. The estate is logistically interesting, close to the training grounds and the military feed warehouse ‘De Fourage’. Throughout the war, several units are billeted here. The official keeping the billeting list last mentions the castle in December 1917.

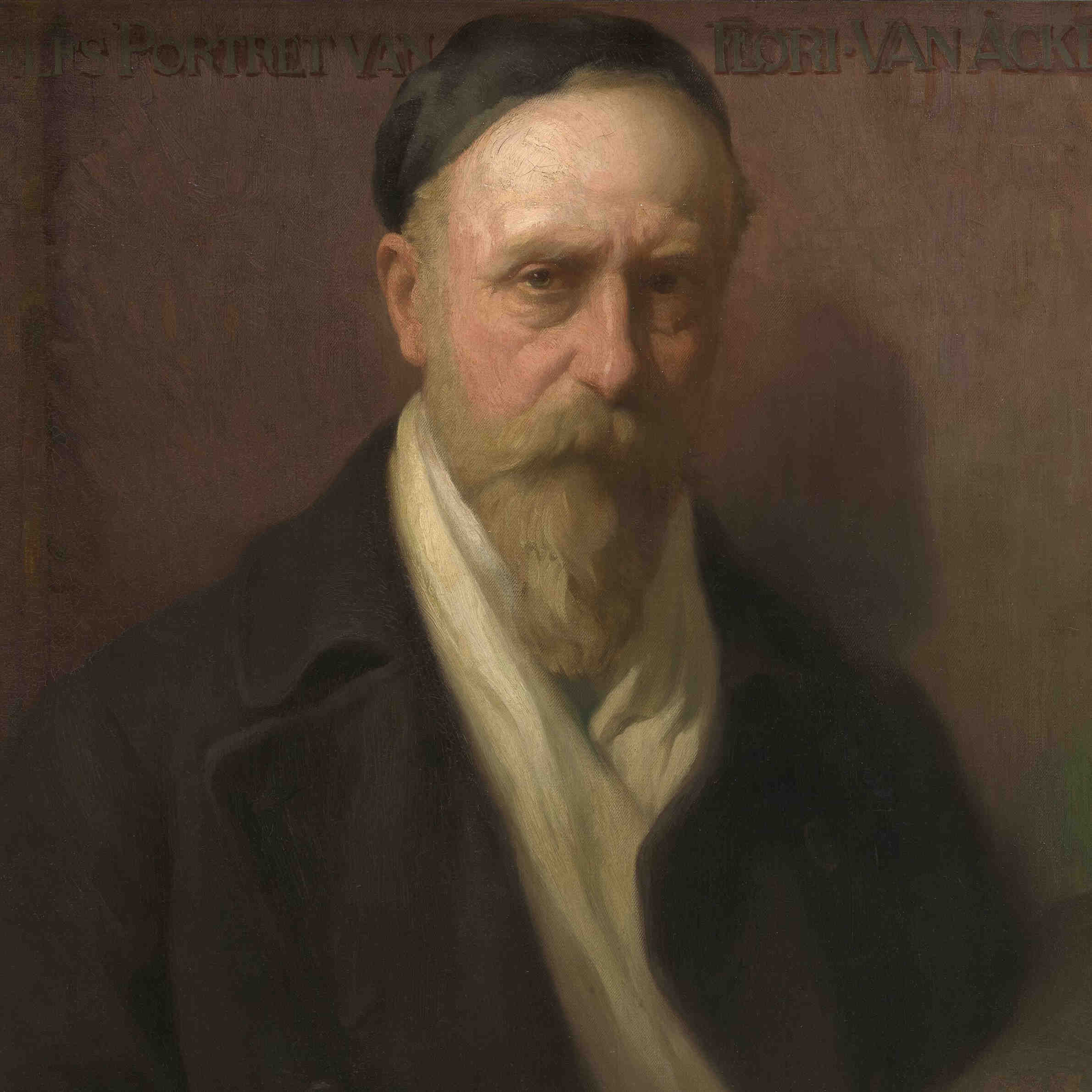

The war and billeting caused damage to Veltem Castle, but there are not many details (the rich “War Damage 1914-1918” archive was destroyed in the 1980s). Only the judgment registers of the war damage courts in Bruges have been preserved. These showed that Gabrielle received a reparation payment of more than 140,000 francs for the damage she suffered. This amount included stolen and damaged movable property, stolen wine, art objects and jewellery. From the original claim file, an expert report has been preserved – by chance. It is the damage report on Joseph Denis Odevaere’s painting in the castle’s cupola room. Artist Flori Van Acker prepared the report after a visit on 10 September 1919.

Van Acker describes his first impression when he entered the castle:

As the castle had been left to the weather elements throughout the war years, the paint was peeling off the ceiling. The billeted soldiers had also damaged the work with gunfire. Van Acker estimated the value of the work at 25,000 francs and the repair work to restore it to its original state at 10,000 francs. On 29 January 1920, experts from the Royal Academy of Antiquities of Belgium examined the cupola room. Their conclusion was that the painting alone had no artistic merit. The badly damaged work was not worth the cost of restoration. But the ensemble of the artwork in the unique Empire castle did form a whole worth protecting. An application was made to protect and restore the work, but it never got that far.

In 1936, the decision was made:

Finally, not only the castle but also the castle park suffered from the German occupation. On 8 December 1916, the German authorities announced the arrival of an expert to designate all usable poplars and walnut trees in the municipality. In the end, they fielded 221 trees from the estate. After the war, Gabrielle de Schietere de Lophem decided to sell her battered castle. The first advertisement for the sale appeared on 22 June 1919. The damage to the castle proved not to be irreparable because by 20 November 1919 it already had new owners. The castle and park went to the Van Canneyt family. Gustaaf Van Canneyt went to live there with his wife and daughter Marie-Jeanne. The castle farm is sold to the former tenants of the farm, the Steevens family. The Interwar period is a period of recovery for the castle farm.

The Second WORLD WAR AND DECLINE

But this quiet period came to an abrupt end in 1940. On 24 April 1940, Gustaaf Van Canneyt died. He was 74 years old. Sixteen days later, German troops crossed the Belgian border for a second time. Unlike World War I, the compensation records for this period have been preserved. These show that the estate suffered no significant damage during the Eighteen-Day Campaign and the first years of the war. The tide turned in Belgium ‘s last year of the war. The damage file of the Van Canneyt family shows that the castle domain underwent two moments of crisis: first around April-May 1944 and then in September ’44.

In the spring of 1944, the German occupation authorities again carried out forced logging on the estate. Emma Van Hauwaert, Gustaaf Van Canneyt’s widow, states after the war that the German troops fielded her trees “to serve as Rommel stakes and [as] barricades in the sea.” The scale of the felling was much larger this time than three decades earlier. A bailiff estimated in May 1945 that they felled a total of 3731 trees, of which 2170 were in the “front forest” near the castle and 1561 in the “back forest”. The boundary between the front and back woods is not described, but is presumably the wide moat that splits the estate into two. Aerial photos clearly show the damage to the tree stock. The felling also damaged hundreds of saplings planted between 1937 and 1943. “All the taillie between them felled” describes the bailiff “and by felling and dragging trees partially ripped out roots…“. During the felling, a tree fell on the pagoda next to the pond. The blow shattered the roof made of Eternit (asbestos). On top of it, the building was ransacked again. The terrace, two windows, two doors, two interior doors, an interior cupboard and masonry also sustained heavy damage. It is unclear whether there was any further attempt to restore the building, but as photos from the 1960s and 1970s show, this is rather unlikely.

In early September 1944, the German troops are on the retreat, but they are still offering fierce resistance in several places. For a second time, the castle residents flee the violence of war. At this time, a German artillery battery decided to set up in the castle grounds. The artillerymen dragged artillery pieces into the park and stayed in the castle. Positioning these guns was no easy task. They broke down parts of the enclosure wall and removed the parapet of a stone bridge at the castle entrance. The footbridge at the pagoda and a bridge over the pond with “rustique railing” were also destroyed. The damage file shows that the estate was also shelled by artillery, presumably in response to German batteries in the castle park. The conservatory received a direct hit and some shells hit the castle. The expert notes the following: “Castle chimney fired with 4 pot pipes and as a result the shale roof was badly damaged.” Several ceilings sustained damage, including in the basement. This was also flooded at the time of estimation. In the vestibule, some columns were damaged ‘en empire’. A 1m80 tall statue of Gilles-Lambert Godecharle, standing there on the stairs, had fallen over. This statue was described in Bertram’s estate description as early as 1826. The damage report concludes the state as follows: “Very old castle and dilapidated.“

From chateau to recreational domain

It will not recover from this devastation. Emma Van Hauwaert died in 1952. Her claim, which would drag on until the end of the 1950s, was taken over by her daughter Marie-Jeanne. Whether the castle was still inhabited after WWII is unclear. Photographs of Veltem taken by local history expert Magda Cafmeyer around 1959-1960 show the estate in a dilapidated state. The end of Veltem Castle coincides with the beginning of its successor: the Interbad. In the mid-1960s, Assebroek, Sint-Kruis and Sijsele were looking for a new swimming pool. Because of the large purchase price, the municipalities decided to work together in a new intercommunal (hence the name). The project was difficult and caused many discussions in the participating municipal councils. The statutes of the intercommunal were submitted in the summer of 1965, but by December of that year a suitable location had still not been found.

It was not until the summer of 1966 that the Veltem domain first appeared in the plans. The choice of Veltem was mainly due to the domain’s location between the three municipalities. The Van Canneyt family sold the domain to Federale Immobilien Vennootschap van het bouwbedrijf N.V, which in turn sold two hectares to the Intercommunale. The remaining nine hectares were to be parceled out. As early as 9 May 1968, the first subdivision plan was ready. Only around the swimming pool and pond would a municipal park be preserved. The castle and all outbuildings were to be razed to the ground. The region around the estate would also be parceled out. Besides several new neighbourhoods to the west and east of the woods, the plans called for Zandtiende, Blauwvoetstraat and Felix Timmermanstraat to continue northwards. The 18th-century castle farm would disappear under the swimming pool car park. With the exception of the neighbourhood around Sprietwegestraat (c. 1995), these plans were never implemented.

The final preliminary draft was submitted on 5 September 1968 and approved in 30 December 1968. The inter-communal association presented the plans and a model of the Interbad to the public in early February 1969. In an interview with Brugsch Handelsblad, alderman Maurits Ramon – the inspirer of the project – describes the choice of location for the new swimming pool. About the castle, bij states the following: “The right place [where the swimming pool will be] is exactly where the castle stands, so it is obvious that the old castle will be demolished soon.” So said, so done. In 1969, the dilapidated Empire castle and all other buildings on the estate disappear under the demolition hammer. Only the grotto and the ruined pagoda remained standing as ornaments for the new park.

The provincial government approved Interbad’s tender dossier in January 1970. The start of construction works took place on 16 March 1970 and the foundation stone was laid on 6 September that year. Even before a stone was straight there were plans to expand the two hectares surrounding the estate to four hectares. This would free up space for an additional outdoor swimming pool and solarium. The plan was to transform the castle park into a modern city park by clearing the excess trees. But this will no longer be decided by the participating municipalities. On 1 January 1971, Sint-Kruis and Assebroek merged with Bruges. This had no major consequences for the Intercommunale, but it did affect the Veltem domain. City of Bruges in fact saw the domain as a green buffer in its rapidly urbanising boroughs. Even before the opening of the Interbad on 27 November 1971, the city bought the remaining park land for the development of a recreational domain. The forest, now ravaged by fly-tipping, was thus spared from subdivision and later refurbished.

Marie-Jeanne Van Canneyt, who last occupied the castle, dies in 1974. Her furniture – the furniture of the former Veltem castle – was sold that summer at Gallery Sioen. This was the end of an era, but also the beginning of a new story. After degradation in the 1960s and early 1970s, Veltem was given a new lease of life. The estate changed from a closed castle park to an open recreational domain. The tightly maintained castle park was reclaimed by nature. Strolling castle dwellers gave way to nature-lovers, playing children and sportsmen. Bertram’s impressive park is a distant memory, but today everyone can enjoy the trees he planted.